This month, I have been blogging about two specific commemorations of Juliette Gordon Low’s life and legacy–the one dollar silver coin coming out in early 2013 and the exhibition at the Texas State Fair put on by the Girl Scouts of Northeast Texas. These are both examples of history being taken out of the four walls of the classroom and made available to all. In my profession, we call that public history. Most people today learn about the past in these ways: memorials (like statues, stamps, and coins), museum exhibits, and–in Juliette Gordon Low’s case–her Birthplace, the Girl Scout First Headquarters, and the Andrew Low House in Savannah, as well as Wellesbourne House in Warwickshire, England.

As a professional historian, I am very interested in the public memorialization of Low. Who is doing it? What tone or slant does it have? Of what does it consist? Who is the audience? How many people do these memorials reach? What will the effect be? I have spoken to various audiences over the past year expressing my hope that someday Juliette Gordon Low will appear in every high school and college textbook. I believe she has been overlooked by history, and as a woman’s historian I hope to, as we used to put it, “write women back into history.” The more public exhibits of her life and legacy, the more likely that is to happen.

Historians strive for objectivity and balance in our treatment of our subjects–hagiography makes us uncomfortable and we prefer to present all sides of a life as supported by evidence we’ve located in the primary and secondary sources. Of course there are many ways to interpret those documents, and skilled historians of good heart can come to very different conclusions when presented with the very same evidence. Honest historians can disagree and both present compelling cases (within reason).

Obviously, the Girl Scouts of the USA have a significant stake in how Juliette Gordon Low is portrayed in exhibits. No organization wants to see its founder be demonized or trivialized–especially when that happens for malicious reasons or because half the facts are missing or the historical context is incomplete. Not that this has happened to Low, in part because the Girl Scouts of the USA keep a close eye on the field. Yet they also understand the importance of free access to the historical record. I was welcomed into Girl Scout archives from Savannah to New York to London. No one at GSUSA authorized my biography, nor did anyone ask me to remove or include information. In contrast, the Boy Scouts would not even let me into their archives.

Public history is a hot field in my profession right now, and surely all historians share the public history goal of making history accessible to everyone. There is also a sub-specialty concerning the history of memorializing, and it seeks to analyze how humans interpret and remember people and events. These two fields come together at the Centennial Exhibition at the Texas State Fair, “Follow the Girls” at the Michigan Historical Museum, and “100 Years and S’More” at the Midland County, Michigan, Historical Society, for example.

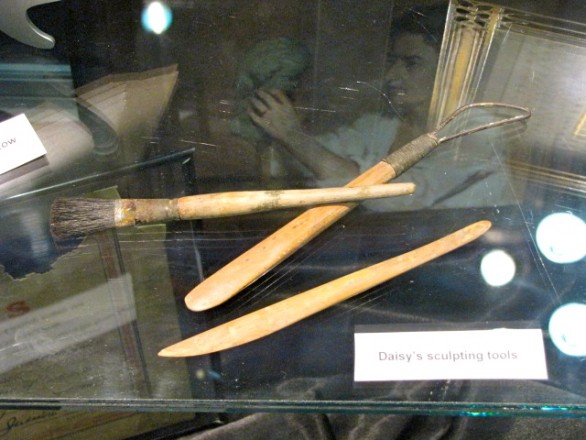

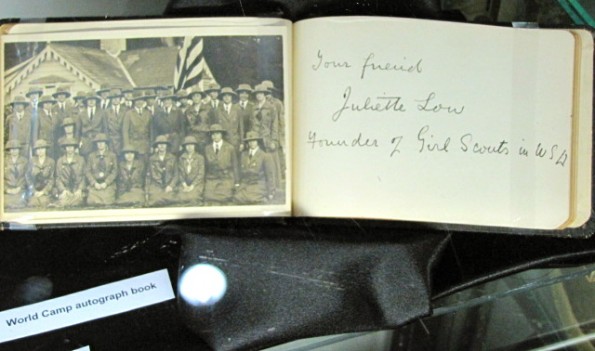

What is so compelling about such exhibits? They are fun. They’re interesting. We love learning from the “stuff” of history–from the sorts of things that the Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace had on display at the Houston convention:

How cool is it to think that she actually wore that hat and sculpted with those exact tools?

Our understanding of Juliette Gordon Low changes subtly when we see artifacts connected with her life, just as our sense of her is deepened when we read her biography. She becomes more real, more human.

What we use to remember her life (in exhibits and in books) depends, of course, on what is available–what has managed to survive. We don’t have her pearls, but we have the story of what happened to them. We do have her hat. We don’t have her car, but we know how she drove. Sometimes, the written word (diaries, letters, meeting minutes, etc.) is all we do have. Fortunately, in Juliette Gordon Low’s case, we also have riches like those pictured above. Crafting them into an exhibit that makes logical sense to the viewer, is honest, visually compelling, historically correct, not too abbreviated and not too wordy, and that also conveys a sense of her personality takes a rare talent. Writing is hard work, but those who create the public history exhibits are unsung heroes. We are all engaged in the same effort of writing Juliette Gordon Low back in to history. Professional historians know that public history sparks people’s interest in reading more about the subject.

It has been my privilege to see several marvelous exhibits during this centennial year, and I take my historian’s hat off to the creative curators and dedicated museum experts who make history come alive in this tangible and thrilling way. Particularly during this special birthday month, during this unique centennial year, I’d like to say thanks to each and every one of them.

California Museum in Sacramento has an exhibit which will close in a week or so. I’ll send you some pictures.

Thank, Sue! Meanwhile–all you out there near to Sacramento go see the exhibit. Unlike a book, once an exhibit is taken down, it is gone forever.

I would like you know that for the 100th year the Heritage

Committee of GS of Greater Los Angeles installed nearly 50 exhibits in libraries and a 6 month exhibit throughout an

historic home in La Canada…and I personally portrayed her

in over 35 events….It was an amazing year! and we are currently building our collections and archives.

Awesome!!!

I love your photos. Especially the hat one! I would love to find a replica of it. Thanks for this posting and the photos too.

Thanks, Betsy! I appreciate your note!