When Daisy and her husband William Mackay Low lived in England, they entertained frequently. Willy Low and his friends were part of what was known as the “smart set.” Mostly aristocrats, all wealthy, they pursued pleasure at the gaming tables, the horse races, and the balls and parties of the social season. When they weren’t in London or off hunting big game in exotic locales, the smart set spent time at their country estates.

The Lows’ home, Wellesbourne House, was a commodious manse located in the Midlands, near to Warwick and Stratford-upon-Avon. Amusing guests who came for long weekends or for several weeks at a time was a job in itself. It was worth it, for the better the entertaining, the higher one’s status among one’s friends. Visitors came to Wellesbourne for horse racing and hunting. But if guests were stuck indoors because of injuries or inclement weather, the options for impromptu pleasure were fewer: whist, bridge, baccarat, board games.

To mitigate his friends’ boredom, and because he loved expensive toys, Willy purchased an amazing object called a Grand Orchestrion. Fifteen-feet high, the Lows’ Grand Orchestrion was a mammoth, mechanical music-making machine. It was related to an organ but with its one hundred wooden pipes could produce the sounds of nearly all the instruments in an orchestra as it played symphonies and concertos for astounded listeners.

The first orchestrion seen in England was displayed at the 1862 London International Exhibition of Industry and Art. These beautiful mechanical instruments were hand assembled and made up of thousands of parts. Sometimes orchestrions had a playable piano keyboard. Eventually paper rolls replaced the bellows that made the sound.

Initially Europe manufacturers like Muckle, Welte, Heinzmann, and Imhof built orchestrions. Since they were the centerpiece of any room that held them, orchestrions were meant to be aesthetically pleasing. They were often highly decorated with painted landscape scenes or stained glass. Some were gilded. Very few were as large as Willy Low’s. Daisy wrote her mother about the difficulty of actually fitting the orchestrion into Wellesbourne House.

Orchestrions were a status symbol that only the wealthy could afford. In Europe, royalty and the aristocracy boasted of their mechanical orchestras. American captains of industry like the Vanderbilts, the Fricks, and the Mellons rushed to own them. Eventually, orchestrions were adapted for public venues to provide background music in fine hotels and spas, and dance tunes in saloons and soda shops.

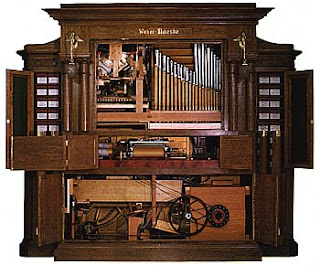

What the Grand Orchestrion that Willy and Daisy Low enjoyed looked like we can’t know. Here, however, is a photograph of one extravagant Grand Orchestrion:

Here’s a look at how the orchestrions opened up (but this instrument surely was not as elegant as the one the Lows owned):

Here is another Grand Orchestrion, a Heizmann, on display at the Black Forest Museum in Triberg, Germany:

If you follow the link, you can hear 46 seconds of the Grand Orchestrion above being played–it’s extraordinary! Imagine Daisy and Willy and their friends listening to such sounds after dinner, or perhaps dancing to the music on a rainy afternoon: Listen to the Orchestrion.

The Lows were almost certainly the only people for miles who owned a Grand Orchestrion. After Willy Low died, his orchestrion was put up for auction. We don’t know what became of it.

_________________

My sincere thanks to orchestrion expert Tim Trager for his kind assistance, especially the information and the photograph about the Heizmann.

I saw one of these this summer in New Orleans, but I had no idea that they would be in individual homes! And the sound… I did not expect it to sound like that. Amazing!

I've learned a lot about orchestrions in the past few weeks! I wish I could hear one live. What stuns me is how tall it would have been–fifteen feet is taller than two tall humans standing on each other's shoulders! Thanks for your comment!!

Wow, Stacy! this is cool!

Thanks, Katherine! I'm really glad you enjoyed this week's blog. Thanks for writing!

http://zaharakos.com/welte2.html

The Zaharakos Ice Cream Palor in Columbus, Indiana has a Welte Orchestrion. It's very loud. I can't imagine having one in a home!

Thanks, Jess–I know, from my research, that they came in all sizes and volumes!